The Next Drug Epidemic is Legal: The Nation's Kratom Problem Is More Complicated—and More Deadly—Than it Seems

Behind kratom's wellness veneer lies a chaotic, largely unregulated market of potent products, soaring use, and mounting evidence of serious harm. A July proposal by the FDA seeks to curb rising addiction by banning the kratom synthetic 7-OH, but critics say it falls short of addressing the broader crisis

Part 1: The "Gas Station Opioid" Crisis

James Kahn struggled with irritable bowel syndrome for most of his life, dealing with severe daily bloating, pain, and frequent diarrhea that made it difficult to live a regular life. After years of shuffling between over-the-counter drugs, a friend introduced Kahn to a green powder supplement he had never heard of before called kratom. Available at local gas stations and smoke shops, the legal substance seemed innocuous enough to try.

For two years, James took a few doses of kratom each day to help improve his stomach symptoms.

"It felt like a miracle. I could finally do my job without worrying about running to the bathroom all the time. Plus, I had more energy and less stress," said James, a 37-year-old energy salesman who lives in New Mexico.

But eventually, his kratom use became a full-blown addiction---after James’ cat died he began a more stressful job, he began consuming higher doses more frequently throughout the day. Though James had no prior history of substance abuse, kratom had given him feelings worth chasing: euphoria, focus, energy, relaxation, and an uplifted mood that would last for a few hours after each dose.

At the height of his use, James was taking up to 100 grams of kratom leaf powder daily. A severe bout of constipation landed him in the emergency room, where doctors did not know what kratom was, assuming this supplement had nothing to do with James' symptoms.

His blood tested positive for oxycodone, a strong prescription opioid he had never taken in his life. James now suspects this was due to high levels of kratom in his blood, which he now knows acts on the same receptors as prescription opioids.

After a few nights in the hospital, James was discharged in the throes of opioid withdrawal and would begin his first attempt to quit kratom. James described the next nine months of quit attempts as "the scariest of his life."

Inside America’s Kratom Problem

Kratom, a leaf native to Southeast Asia, has quietly become one of the most widely-used psychoactive substances in America. The FDA has kept the substance in a legal grey since its introduction in the U.S., stating that “kratom is not lawfully marketed as a drug product, dietary supplement, or food additive”.

But somehow, it is still sold.

According to one recent estimate, roughly 9% of Americans, or 25–30 million people, now use kratom, and over 80% of tobacco and vape stores in all 44 kratom‑legal states sell the product.

Acting like an opioid, kratom binds to the same receptors targeted by fentanyl and other opioids. Its use can lead to addiction and severe health problems, including liver toxicity, seizures, cardiac arrest, and respiratory depression.

Earlier this year, the federal government announced in July its intent to ban the synthetic kratom derivative product 7‑hydroxymitragynine, also known as 7‑OH, citing its high addictive potential and opioid‑like effects. Unlike natural kratom and its older extracts, 7‑OH can be 13 times stronger than morphine, according to a new FDA toxicology report cited during the federal announcement.

But all other kratom products, including traditional extracts with higher potencies and other strong synthetic derivatives, will be left untouched, said officials at the United States Drug Enforcement Agency and the Food and Drug Administration.

Pro‑kratom advocacy groups say 7‑OH should be categorized separately from other kratom products, leaving “natural kratom” legal for purchase nationwide. Kratom researchers and regulatory officials have long listened to the positions of two key organizations: the Global Kratom Coalition and the American Kratom Association. Both groups have been instrumental in keeping kratom legal over the last two decades, and have deep financial ties to key kratom researchers conducting safety studies and the federal and state government officials in charge of regulating the substance.

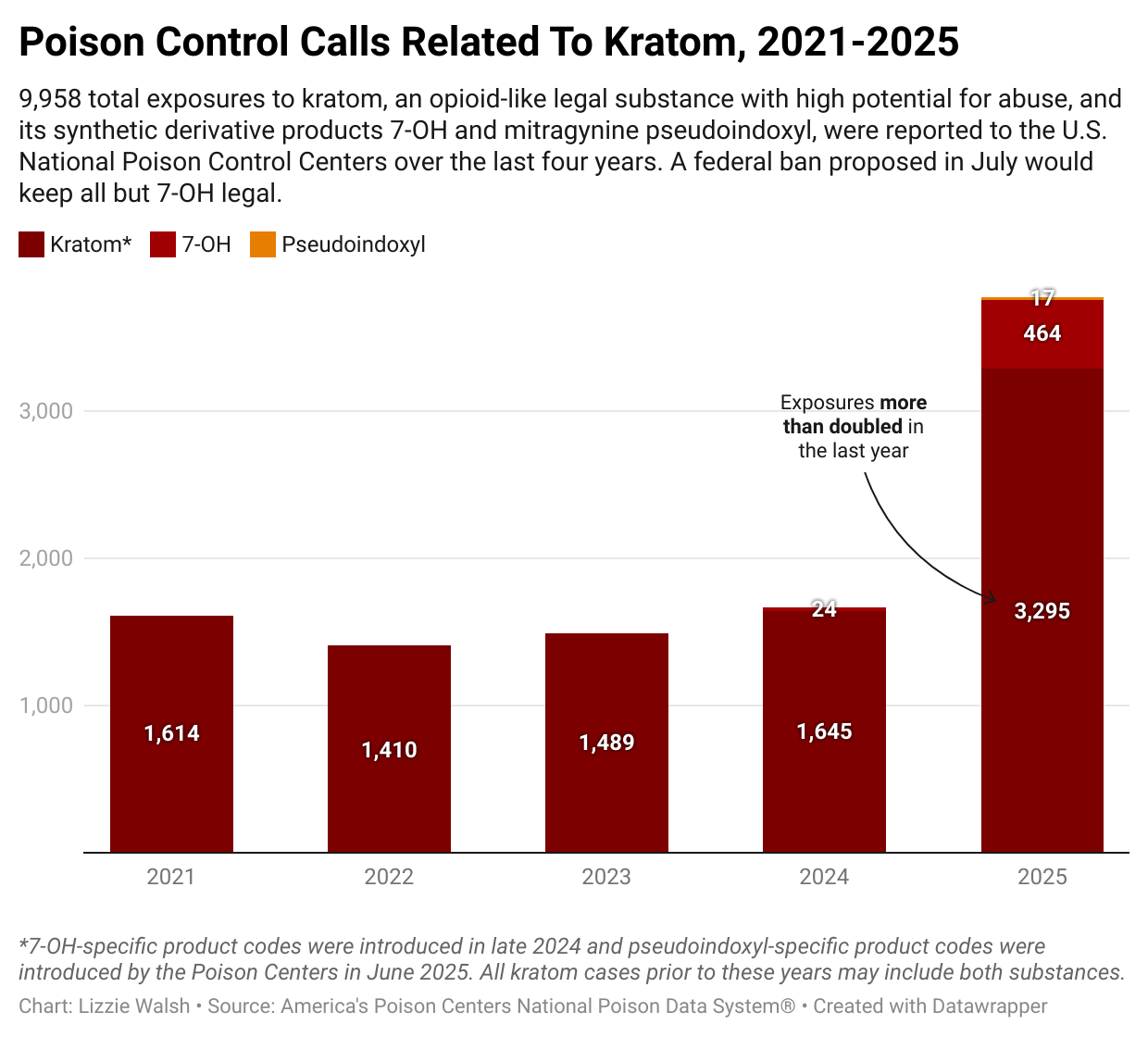

In the first six months of 2025, kratom‑related poison cases already surpassed totals from 2024, with reports including toxicity, drug abuse, and seizures. Rehabilitation centers report a surge in kratom‑related detox admissions, while recovery communities grow in size. Treatment experts and former kratom users warn that without comprehensive, long‑term studies on safety, such federal actions may not stop new addictions—and may even drive demand for stronger derivatives. Interviews with researchers, clinicians, and users depict a system where doctors often don’t recognize kratom, consumers unknowingly get hooked, and federal actions stop short of addressing the crisis.

More Than An Opioid: Kratom’s Chemical Chaos

Kratom has been known to the western world since the 1830s, and its traditional use differs greatly from how the United States consumes it today. Kratom is a tropical tree in the coffee family native to Southeast Asia, historically used by day laborers seeking its stimulant and pain‑relief properties, as an herbal medicine for common ailments, and as an alternative to opium. Now illegal in its countries of origin due to its addictive properties, kratom was traditionally consumed by chewing or steeping its leaves in tea.

According to Dr. Charles White, who has been studying kratom and its effects for decades, historical consumption of kratom produced a far weaker effect than contemporary kratom products today. The U.S. was first introduced to kratom in the 1970s, when Vietnam War veterans who used the leaf to ease opium withdrawal symptoms brought it back home. It wasn’t until the 2000s that new formulations of kratom, like high‑potency extracts, began to change the market and consumer use patterns, said White, a distinguished professor at University of Connecticut’s School of Pharmacy. Since its introduction in the United States, all kratom products have been federally legal for purchase without a license.

It wasn’t until 2016, when a failed attempt by the DEA to make all kratom products a Schedule 1 drug was overturned by community pushback, that the kratom market exploded. There were nine times more kratom exposure cases in the U.S. in 2018 than in 2017, according to FDA data, and interception of illegal kratom imports tripled globally. What was once a niche import industry of around $6 billion is now projected to have a market value of $22 billion by 2035 thanks to product diversification, lax regulatory guardrails, and increased consumer awareness.

Kratom products come in a wide range of formulations, from leaf powder to liquid shots, and can produce a wide range of serious effects depending on their ingredients and potency. Kratom has over forty known alkaloids, naturally occurring compounds in the leaf that have varying effects on the brain and body. Unlike heroin, which is a single‑molecule chemical that mainly acts on one key opioid receptor, new research shows that kratom’s alkaloids act on multiple opioid receptors at a lower strength than heroin, and also affect the body’s energy and pleasure hormones adrenaline, serotonin, and dopamine.

Research shows kratom can cause acute liver and kidney injury, in addition to heart, stomach, brain, and mental health problems. Though clinical research is limited, a combination of research studies show natural kratom can act like an opioid, a stimulant like Adderall, a serotonin-targeting depression/anxiety medication like Lexapro, and a benzodiazepine like Xanax, all at once. This makes it incredibly dangerous, especially when mixed with other psychoactive substances or certain prescription medications, according to kratom treatment expert Dr. Casey Grover, MD.

“I have a lot of patients who have never been addicted to drugs, but quickly become dependent on kratom because it’s legal and it gives them pain relief, energy, and euphoria all at once,” says Grover, who treats patients with kratom use disorder in California and hosts an addiction medicine podcast called “Addiction Made Easy.”

“When they figure out that it’s an addictive, opioid‑like substance, they always say ‘if I knew what this was I never would have gotten started.’”

“The labels on these products say stuff like ‘an all‑in‑one energizing life‑lifter’, with no addiction warnings and often no serving sizes. The dependence is what gets people stuck, but the second part is that it is an obscure supplement that so few healthcare professionals know about,” Grover says.

But the discussion around regulating or banning kratom has been stymied by contradicting views. Some users credit kratom with helping them quit prescription opioids, while others develop decades‑long addictions costing hundreds of thousands of dollars, with some hospitalized or even killed by strong derivatives or raw leaf alone. Limited data on overdoses and side effects due to insufficient research, patchwork regulation, and lack of adequate knowledge among the majority of clinicians. leaves federal and state agencies ill‑equipped to respond, even as the industry continues to expand.

Despite Widespread Use, Kratom Data is Limited

The patchwork of kratom products, legal statuses, and limited medical knowledge makes data collection difficult. Poison control centers did not start to report kratom cases until 2015, and only 1,503 cases have ever been reported to the FDA’s drug‑event database FAERS—despite reports that U.S. kratom use is common and widespread.

Of these FDA‑reported kratom cases, 93% resulted in serious outcomes, and half resulted in death. Only one case reported no other substance use. But because FAERS reports are not mandatory and kratom products rarely contain detailed and accurate ingredient labels, conclusions about kratom’s health effects are hard to draw.

And as serious adverse events are also more likely to be reported by consumers and healthcare professionals alike, this data cannot broadly represent an average kratom response.

“There are many problems with kratom case data: sometimes consumers don’t mention the other drugs they’re taking in these reports, and Poison Control didn’t separate 7‑OH from the broader kratom category until last year, so it's hard to say which kratom products are creating what side effects,” says Grundmann.

The National Poison Control Centers data paint a more comprehensive, but still limited, picture. Nearly 10,000 total calls related to kratom product exposures have been reported since 2021, and 95% of these exposures were due to “natural kratom”, a definition only recently created to describe all non-7-OH or other synthetic kratom offshoot products.

The FDA says natural kratom will not be targeted in the proposed ban.

Poison Control didn’t begin to separately categorize synthetic kratom products like 7‑OH until late 2024, and data on the first sales of 7‑OH‑specific products are hard to find.

The isolated compound derived from the kratom plant didn’t begin to make major headlines until July 2025, though some reports say 7‑OH products have been sold since 2023. In the last year, Poison Control exposures to natural kratom products have more than doubled. Thirteen percent of all 2025 exposure cases were in people under 19 years of age.

Key advocacy groups run by kratom industry leaders have kept the plant broadly legal, arguing only its derivatives like 7‑hydroxymitragynine be banned. But of kratom’s 25 million estimated daily users, those who say they fell victim to the broadly unregulated, understudied, and extremely addictive product say the legal “gas station heroin” can ruin lives.

A Withdrawal Unlike Any Other

James first purchased kratom through the suggestion of his friend at what he thought was a “medical facility” in Lakewood, Colorado called MyCleanKratom. As a health enthusiast, James was convinced by the medical certificates lining the lobby’s walls and the “safety” language on their website that suggested the facility was a legitimate medical venture.

“They claimed to have medical expertise on the use of kratom, and they asked me about my health concerns. It wasn’t until later that I realized I was getting hoodwinked by a pseudo‑doctor selling an unregulated, addictive supplement,” said James.

After James’s trip to the emergency room, he returned home and felt the full brunt of kratom withdrawal: a combination of typical opioid detox symptoms combined with brain‑breaking stimulant withdrawals. “I went home and looked in the mirror, my eyeballs were like saucers. Restless legs, vomiting, nausea, diarrhea, lack of appetite, no sleep for 2+ weeks not even an hour, all alone,” he said.

It wasn’t until late December that he was able to exercise again, but he still felt an unshakeable depression every hour of the day. This is what treatment experts describe as the “PAWS Phase”, or Post‑Acute Withdrawal Syndrome, which occurs with other opioid detoxes. Though research is limited, studies and user reports show that kratom‑related PAWS is generally characterized by insomnia, depression, severe anxiety, fatigue, inability to feel pleasure, poor appetite, low motivation, and suicidal ideation.

“I’ve been addicted to every drug, and I’ve quit every drug. And kratom was the worst detox I’ve ever had,” said comedian Jason Ellis in a July Instagram video post.

After months of PAWS where his daily run became the only thing he looked forward to, James sustained a leg injury that required surgery and months of rest and recovery. This was when he reached out to a provider for medical treatment for his depression, who first put him on ketamine therapy. It didn’t help, and was just the beginning of what James described as a “pharmaceutical guinea‑pig situation.”

“I was on Xanax, then Lexapro, then bipolar meds. They didn’t work, and I developed an uncontrollable movement disorder after quitting the bipolar medication, even though I was only on it for 10 days. Basically, I was suicidal, having gone through all these drugs to help PAWS. Nothing worked until I got on suboxone,” says James.

Suboxone, a medication prescribed to treat opioid use disorder, has become one of the key ways doctors help people hooked on kratom users who have relapsed many times and haven’t been successful quitting kratom on their own.

Suboxone is a partial opioid agonist that blocks the effects of kratom and other opioids, and has historically been used to help patients with heroin and other opioid addictions. Recent case studies report its promise as a treatment for Kratom Use Disorder and safer alternative to long‑term kratom use.

William Eggleston, Director of New York State’s Poison Control Center that serves all state counties except NYC, has been managing kratom cases in New York State for over a decade. “We have a consistent volume of kratom cases year over year. The change recently is around folks buying drinks instead of powder, but how we treat these patients depends on how long and how much they are using,” says Eggleston.

The Poison Center triages patients with kratom overdoses and withdrawal symptoms, sending them to the ER for naloxone treatment—a drug used to reverse opioid overdoses that he says is effective with kratom cases—or connecting them to outpatient addiction care. He says these patients are treated just like those overdosing from stronger opioids like heroin and fentanyl.

“The claim that kratom is safer because it doesn’t cause respiratory depression like other opioids is just not true. We may see it less often, but it happens with raw kratom powder, with 7‑OH—any kind of kratom product. And unlike with fentanyl, we often see seizures with kratom use,” says Eggleston.

Despite claims from the federal government that non‑synthetic kratom is relatively safe, research shows that leaf kratom can have serious side effects. Kratom powder products have a higher volume than extracts, which can overload the gastrointestinal tract, kidney, and liver if taken regularly or in high amounts. Studies show kratom use can cause acute liver and kidney injury, in addition to heart, stomach, brain, and mental health problems.

After James had gotten free of his kratom addiction, he made it his mission to help others who knew little about the plant they now needed to function. It didn’t matter how or why they started to use kratom; the people who tried to get off of kratom couldn’t talk to doctors, friends, or family.

James is now on a low dose of suboxone, which he credits to helping him quit a nicotine addiction in addition to kratom. He plans to taper down on suboxone in the coming months before stopping use, saying that suboxone saved his life. “Maybe there are medical uses for kratom, I don’t know. We need more research on it, but first, we need to educate doctors and patients. If kratom was banned, I never would have had an addiction like this, and I never would have sought out drugs,” said James.

From Leaf to Laboratory: The Market Evolution

Kratom’s two compounds mitragynine and 7‑hydroxymitragynine, also known as 7‑OH, are most responsible) for the narcotic and stimulant effects of kratom. These compounds both target the μ‑opioid receptor, the same receptor that other opioids like Oxycontin and fentanyl target—but at different potency levels.

When mitragynine extract products—referred to as “kratom extracts” to distinguish from newer synthetic forms made of 7‑OH—hit the market in the late 2000s, a combination of surveys and new consumer use data show a massive increase in kratom consumption. The kratom market is projected to grow from $2.19 billion in 2024 to $23 billion by 2035, with extract products comprising more than a third of the market.

Highly potent, portable, and easy to consume, these liquid shots and chewable gummies contain between three and eight times more mitragynine than raw leaf powder by volume.

“There have only been 17 published clinical trials on natural kratom leaf, and no actual clinical trials have been done on extracts,” says Matthew Lowe, director of the kratom advocacy group Global Kratom Coalition. The bulk of these clinical trials were funded by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse for kratom research, with the University of Florida School of Pharmacy receiving $6 million in funds over two years.

Then came 7‑OH. The first research on the compound emerged thirty years ago. A 2009 study explains the influence of 7‑OH on kratom’s morphine‑like sedating effects: “mitragynine’s weak potency cannot explain the kratom’s potent opium‑like effects” and that the opioid‑like effects were “mostly based on the activity” of 7‑OH. The study concluded: “Kratom is widespread and easily available via the Internet…the abuse of these plant products is a matter of serious concern.”

But it wasn’t until May of this year that the American Kratom Association (AKA), one of the two leading pro‑kratom advocacy organizations, submitted 18 complaints to the FDA reporting vendors selling chemically manipulated 7‑OH and two other kratom derivatives.

The difference in opioid‑like effects of a traditional kratom extract compared to a 7‑OH extract is significant—7‑OH is 10–20 times more potent than mitragynine, and user anecdotes report the synthetic product is far more addictive than a typical kratom extract. Requiring highly controlled lab conditions and a more complex extraction process than mitragynine, 7‑OH has recently been manufactured on its own in the form of tablets, shots, and even ice cream cone‑like candy by many of the top kratom leaf companies.

Price points of kratom products vary from $8–$20 for liquid kratom shots and $10–$40 for powders. 7‑OH’s higher addictive potential combined with an average price point of $30–$80 for a standard small‑to‑medium size pack of pressed tablets has made addiction to the product both look and feel like a street drug. Some users report spending between $150 and $600 per day at the height of their 7‑OH addiction.

On December 2, a 26‑year‑old Utah man died of a 7‑OH overdose after taking two pills he received for free from a smoke shop. The national poison centers report 464 exposures to 7‑OH reported in 2025 alone, more than double the previous year, with 67% of those exposures requiring treatment at a healthcare facility.

Though the federal government seeks to ban the dangerous 7‑OH from being sold, “natural” kratom products still make up 95% of poison control cases reported year over year. And some of these natural products might not be so natural after all.

Part 2: Keeping Kratom Legal: The Shell Companies and the Advocacy Machine

The Little Blue Bottle That Changed Everything

Before these derivatives, kratom was a niche, powdered green drug available in some smoke shops. It wasn’t until the combination extract drink FeelFree, a small blue bottle that became broadly accessible in gas stations nationwide in 2020, that kratom became commercially popularized.

Manufactured by a company called BotanicTonics, FeelFree includes both kratom and kava, a psychoactive plant that raises the potential for addiction when used with kratom. The shot was originally introduced to the market at 7‑Eleven stores, shelved next to energy drink shots near the register, and was one of the first products to move from smoke shop seclusion to national chain publicity. A press release from BotanicTonics celebrated the kratom shot’s ascendance to #1 convenience store energy drink in December 2023, and the company received “top manufacturer” status among energy drink gas station manufacturers in 2024. Between 2023 and 2024, sales of the product more than tripled.

In late 2023, California resident Romulo Torres, who became addicted to FeelFree and experienced psychosis, delirium, and loss of consciousness, filed a class‑action lawsuit against 7-Eleven.

BotanicTonics was found guilty of the harm Torres and others testified to, and the company has since paid $8 million dollars in settlement funds and raised the minimum age for FeelFree purchase to 21.

The suit prompted FeelFree’s removal from 7‑Eleven stores, but by then the company had already launched FeelFree at 600 CircleK locations. By 2024, the number of stores selling FeelFree more than doubled, surpassing sales of 5‑Hour Energy shots and Ghost energy drinks.

By March 2025, annual profits from the kratom product ballooned to a quarter of a billion dollars according to BotanicTonics, and FeelFree reached the number one product status in the energy drink and supplement category according to Nielsen IQ data.

Upstate Poison Center Director Eggleston says that despite databases lumping together “wellness supplements” like FeelFree and other kratom products like 7‑OH, he suspects FeelFree’s wide availability and marketing has partially driven the increase in reported kratom cases. “The two biggest changes recently: rather than folks buying powder, they are buying wellness drinks and those are easily accessible, not well labeled, and folks are using kratom without knowledge,” said Eggleston.

Social media posts report children approaching adults at gas stations and asking them to buy them FeelFree, while Facebook posts warn parents of the product accessible to teenagers. Despite the company’s recent message to retailers not to sell FeelFree to those under 21, the non‑FDA regulated product is not subject to age limit enforcement like alcohol or cigarettes.

An anonymous employee of BotanicTonics who was interviewed for the Kratom Sobriety podcast, a show that amplifies awareness around kratom addiction and recovery, says the company’s practice of giving six free samples to each store allowed him to afford his own addiction to the product he was selling. “I started to realize it’s not an energy drink and it’s destroying people’s lives. When stores sell out, it’s a couple of people buying half a dozen bottles a day, spending hundreds of dollars,” said the whistleblower, who was employed by the company to sell the kratom/kava beverage to some of the 30,000 stores that carry it nationwide.

FeelFree gained traction on social media in the past year, with users like Jasmine going viral for her story about drinking nine to twelve bottles, or up to 24 “servings”, daily at the height of her years‑long addiction to the drink. The company previously advertised their product on TikTok and other social media platforms before a slew of negative comments and videos claiming harm and addiction from the product flooded the company’s posts.

“FeelFree inspired other companies to make money and market kratom in the same way. It was the first product to target the all‑natural consumer near the checkout counter, changing the market forever. There’s no putting that back in the box,” says Theresa Perry, a professor of economics at California State University, San Bernardino and author of multiple studies on kratom consumption trends.

“What we’ve seen is that people did consume kratom before FeelFree, but most consumers were carefully researching it as a substitute for opioids and pain. But with FeelFree, this is when a massive amount of consumers who have never heard of kratom began to use it—regularly, and often,” says Perry.

The past ten years of the kratom industry shows that this plant and its myriad, understudied compounds have been manipulated to create new addictive substances with a high potential for abuse and profit. But how did FeelFree gain such massive commercial success at just the right time?

Reports, press releases, and lobbying documents show that some kratom companies knew exactly when legal gray-areas would provide a fertile ground for product sales—because they created the legislation themselves.

The American Kratom Association’s War Chest

While many pro-kratom consumer advocacy groups exist in the U.S., the Global Kratom Coalition and the American Kratom Association have had the most impact on legislation and kratom industry profit. They have pioneered state kratom access laws, donated to state representative campaigns supporting kratom access, and have worked directly with the U.S. Department of Agriculture to draft new positions on 7-OH.

Research shows that the groups’ leaders—the nonprofit executives directing the national kratom conversation for over a decade—are directly tied to the kratom companies they have long helped stay profitable, including manufacturers profiled in the Tampa Bay Times’ “Deadly Dose” investigation and other reporting on opaque supply chains and shell companies.

After the FDA announced its request that the DEA list the substance as a Schedule 1 narcotic in 2016, consumers and industry advocates fought to keep the product legal. A “March for Kratom” protest in D.C., a consumer petition with over 130,000 signatures, and a flurry of lobbying helped push the DEA to withdraw its proposal—but a combination of lobbying records and official statements from DEA show the ban’s reversal was orchestrated by two tax‑exempt nonprofit organizations with ties to kratom manufacturers and Congress.

This failed regulation attempt allowed the industry to freely expand, and kratom is now regulated in a patchwork of county and state laws. Only six states have banned the sale or possession of kratom, while other states have county‑by‑county bans or age‑limit restrictions. Today, 26 states have no regulations on kratom products whatsoever.

The other major pro‑kratom advocacy group, the American Kratom Association, was established in 2014 as a 501(c)4 tax‑exempt nonprofit by Susan Ash. According to a press release written by American Kratom Association lobbyist Mac Haddow, Ash’s motto for kratom advocacy was “Endless Pressure, Endlessly Applied”. Ash also said that the AKA “lobbied too much to become a tax-deductible organization”.

Ash said she started the AKA when she found that kratom helped treat her Lyme disease. Ash stepped down from Board chair in 2016 after an internal audit found “significant discrepancies and missing records” in financial documentation for compensation and expense reimbursements paid to her over a significant time period.

Ash spoke about being silenced by her own Association and argued on a pro-kratom podcast that since leaving, the Association is improperly using and accounting for their funds.

The Association was a key figure in reversing the federal ban on kratom in 2016, spending $4.4 million on the creation of 34 nearly‑identical state bills that preserve the right to purchase and sell kratom, later summarized in state law compilations. These laws allow manufacturers to sell kratom without first conducting safety studies, and don’t require labels that disclose potency or warn consumers of risk.

Former Republican Congressman of Arizona Matt Salmon took on the task of convincing Congress to oppose the ban, persuading over 60 members of Congress to sign a letter to DEA. Salmon announced his retirement from politics in February of 2016, just months before the DEA officially announced the ban’s withdrawal. In 2020, Salmon became the AKA’s Chairman of the Board.

The Association’s 2024 tax records show $2.3 million of the organization’s total $4.4 million expenses were spent on educating lawmakers about kratom policy. Other expenses include public relations spending to “improve the public perception of kratom.”

The AKA also donated a cumulative $25,250 to The Republican Senate Campaign Committee of Utah between 2021 and 2024. Utah not only legalized kratom but regulated it under the Kratom Consumer Protection Act. The regulations ensure the purity of kratom by prohibiting any heavy metals or bacteria in the drug supply, and mandating that retailers of kratom register their business appropriately. This emphasis on “purity” does nothing to address the safety of the substance itself, as federal health agencies continue to document hundreds of kratom‑linked deaths.

Even after the ban was reversed, the AKA continued to fight claims that kratom caused the 25 FDA‑reported deaths associated with kratom exposures, saying the deaths were a coincidence and not caused by kratom. The death count in the FDA’s database is now 748.

In the wake of increased calls to regulate or ban 7‑OH, the organization has shifted their position—instead of broadly endorsing the legality of all kratom and kratom‑derivative products, the AKA now says products with 7‑OH concentrations above 2% should not be deemed “true kratom”.

A recent Washington state court filing argues that major kratom manufacturers Whole Herbs, Remarkable Herbs, and OPMS are all owned by OLISTICA, an “evolving web of shell entities and fictitious business names” that funded and shaped the American Kratom Association from the very beginning. The filing claims that these companies have used the AKA’s “certified vendor” label to bolster legitimacy, and shield themselves from the harms caused by their kratom products through a “complex web” of secret trade names that link to nowhere.

A 2022 investigation by Courthouse News Service also exposed the Association’s attempt to deny that any deaths could be attributed to kratom alone.

The Global Kratom Coalition, FeelFree, and the New Crackdown

Before concentrated 7‑OH products drew intense regulatory and media scrutiny, both the American Kratom Association and the Global Kratom Coalition promoted broad legal access to kratom products, focusing their advocacy on blocking bans and passing “consumer protection” laws rather than drawing sharp distinctions among different types of kratom preparations.

After a spike in claims about kratom deaths and addiction on social media in the last few years, both organizations have become vocal about banning 7-OH after reports harms arose—though adulterated 7-OH in kratom products has been publicly known since 2009. The groups have fought over who had or had not previously advocated for 7-OH access despite sharing historically-similar views and lobbyist Mac Haddow.

In July, HHS Director Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. announced his intention to ban 7‑OH and other synthetic derivatives, as well as kratom powder above 2% mitragynine, in a federal crackdown that followed high‑profile media coverage and FDA action on 7‑OH products. After outcries about FeelFree’s dangers, Ross and his advocacy organization have pivoted their stance on kratom access, loudly pushed back against 7‑OH. The organization claims that it should not be labeled as a “kratom product” and supports a federal ban of the substance, echoing positions in its 7‑OH statements and social‑media posts.

J.W. Ross has used litigation to divert national attention from the Coalition’s ties to kratom manufacturers’ addictive products. Ross and the GKC have contributed funds to California state representative Matt Haney’s campaign in 2024, who introduced a ban on 7‑OH in California.

Recently, a flood of extremely similar legislation around kratom access have reached state desks. Known as “Kratom Consumer Protection Acts”, these state bills drafted by the AKA and GKC are designed to ban 7‑OH and other synthetic products, promote purity standards in “real” kratom, require ingredient and warning labels on products, and restrict the age of sale to 21, mirroring provisions in the proposed Federal Kratom Consumer Protection Act. This or similar acts have since been passed in 14 states including Arizona and are pending in others including New York.

There’s a thin line dividing the policies of the GKC and AKA. Both groups advocate for broad legal access to kratom and support “purity standards” for manufacturers, both were founded by kratom business magnates, and have even shared lobbyists and political consultants. The GKC believes all kratom derivative products like 7‑OH should not be considered kratom and should be regulated as drugs, while the AKA now believes kratom derivatives with over 2% a concentration of 7‑OH should remain a legal supplement.

For the AKA, at least, this is a shift from its prior policy recommendation to keep every kratom product legal nationwide.

But the shifting positions of the groups, both led by kratom business leaders, seem to be dictated by the financial interests of manufacturers. As the two biggest players in the kratom industry, both seem to be trying to end up on the right side of history while preserving the financial goals of the companies that founded them, a pattern echoed in investigative reporting on kratom lobbying and profits and industry‑funded legislation.

What some independent kratom treatment providers, unaffiliated researchers, and consumers agree on is that the positions of the two advocacy groups don’t seem to align with goals to preserve public health in the U.S. and abroad. Instead they’re at the mercy of their stakeholders—the kratom companies themselves, as reflected in clinical and public‑health warnings about kratom harms and rising calls for tighter regulation.

“The consequences of a ban versus a looser regulation are complex for those already addicted, as they will need addiction resources to help with recovery. They may be able to order it online from other places, or from a black market that arises after the ban. But a ban protects the under‑informed consumer who might accidentally get addicted,” says Dr. Casey Grover, MD, an addiction medicine specialist, who has no financial conflicts of interest with the two advocacy organizations, in recent coverage of kratom addiction and policy.

For now, there is no national regulatory framework for kratom products, though some states are working to pass Kratom Consumer Protection Acts drafted by advocacy organizations tied to the industry.

As of December 2025, the DEA is reviewing the FDA’s 7-OH ban proposal. Once a DEA decision is made, the agency will initiate a formal legislation process that will include a 60-day public comment period. If the ban is passed, kratom itself as well as other kratom synthetics with high potential for abuse, like mitragynine pseudoindoxyl and MGM-15 will remain.

Typically, legislators making key public health decisions rely on a wide range of peer-reviewed research and take into account conflicts of interest. When regulatory bodies instead rely on a small number of powerful voices who stand to be financially enriched if their policies are implemented, citizens get left behind, as warned in both academic analyses of kratom policy and FDA communications.

“If you want to ban cocaine, you’re gonna have to ban the coca plant. Banning 7-OH while leaving kratom available means we’re going to see people cooking the leaf, making 7OH and other synthetics on their own—because that's legal,” says James.